When the Confederate Post Office Department took over the operation of the postal system in the Confederate States on 1 June 1861, there were no postage stamps. Postage stamps would not become available until October; it would be another few months before they were available at all post offices.

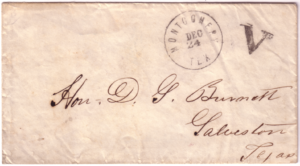

To accommodate postal customers, postmasters reverted to the practice that was used before stamps were introduced in the United States in 1847. Individuals desiring to mail a letter had to take it to the post office where the clerk would collect the necessary postage and mark the letter paid and the amount of postage. The marking was either done by handstamp or in manuscript.

Click any image to enlarge

One would expect such stampless uses would end when postage stamps became available. This is not true. The Confederate Post Office Department experienced a constant shortage of postage stamps as evidenced by the number of stampless uses throughout the war. A large variety of handstamped markings were used, particularly by the larger towns.

Regulations required that stampless letters be marked as paid with the amount of postage paid. As the war progressed, postmasters began to take shortcuts. Sometimes letters were just marked “Paid.” Other times only a rate marking was applied. The latter was against postal regulations as all mail was to be prepaid, except those from postal officials and from soldiers after July 1861. Examples of each are shown below.

Also considered stampless markings are “due” and “free” markings. Due markings are found most often on soldiers’ letters, although the marking is also found on some regular mail. Bureau chiefs and other officials at the Post Office Department as well as town postmasters used a “free” marking on official business letters. Two examples are illustrated below: